Recording

Abstract

Video is hard, and reliable timestamps in increasingly virtual environments are even harder.

We at Mux recently broke ground on a new live video experience, one that takes a website URL as input and outputs a livestream. We call it Web Inputs. As with any abstraction, Web Inputs hides quite a bit of complexity, so it wasn’t long before we ran up against our first “unexpected behavior”: our audio and video streams were out of sync.

This talk walks you through our experience triaging our timestamps troubles. It’s a narrative account that puts equal weight on the debugging process as the final implementation, and aims to leave the audience with a new perspective on the triage process.

I hope you’ll learn from our mistakes, a bit about Libav audio device decoders, and hopefully a new pattern for web-to-video streaming.

Transcript

Hey everyone, my name is Walker Griggs, and I’m an engineer at Mux.

I’m actually going to do something a little out of order here and introduce the “punchline” for my talk before I even introduce the topic.

The punchline is: “reliable timestamps when livestreaming from virtual environments are really, really hard.”

I’m giving the punchline away because this talk isn’t about the conclusion, it’s about the story I’m going to tell you. It’s a story about our mistakes, a little bit about Libav audio device decoders, and a lot a-bit about some good, old-fashion detective work.

One last piece of framing: up until I joined Mux 9 months ago, I worked with databases. That was a simpler time. WHIP still meant whipped cream and DASH was still 100 meters.

I’ve realized, though, that databases and video have a lot more in common than you might think. They’re both sufficiently complex pillars of the modern internet, they both require a degree of subject matter expertise, and, at first glance, neither are exceptionally transparent.

That’s why this talk will be geared to those of us who are looking to level up our deductive reasoning skills and maybe add new triage tools to our tool box. In the end of the day, all that matters is “getting there”.

So where is this talk going?

We’ll start by introducing the problem space, of course. Every good story needs an antagonist. We’ll take a quick detour to talk about timestamps, and use that info to color how we triaged the problem. Finally, we’ll arrive back at our problem statement and how we fixed it.

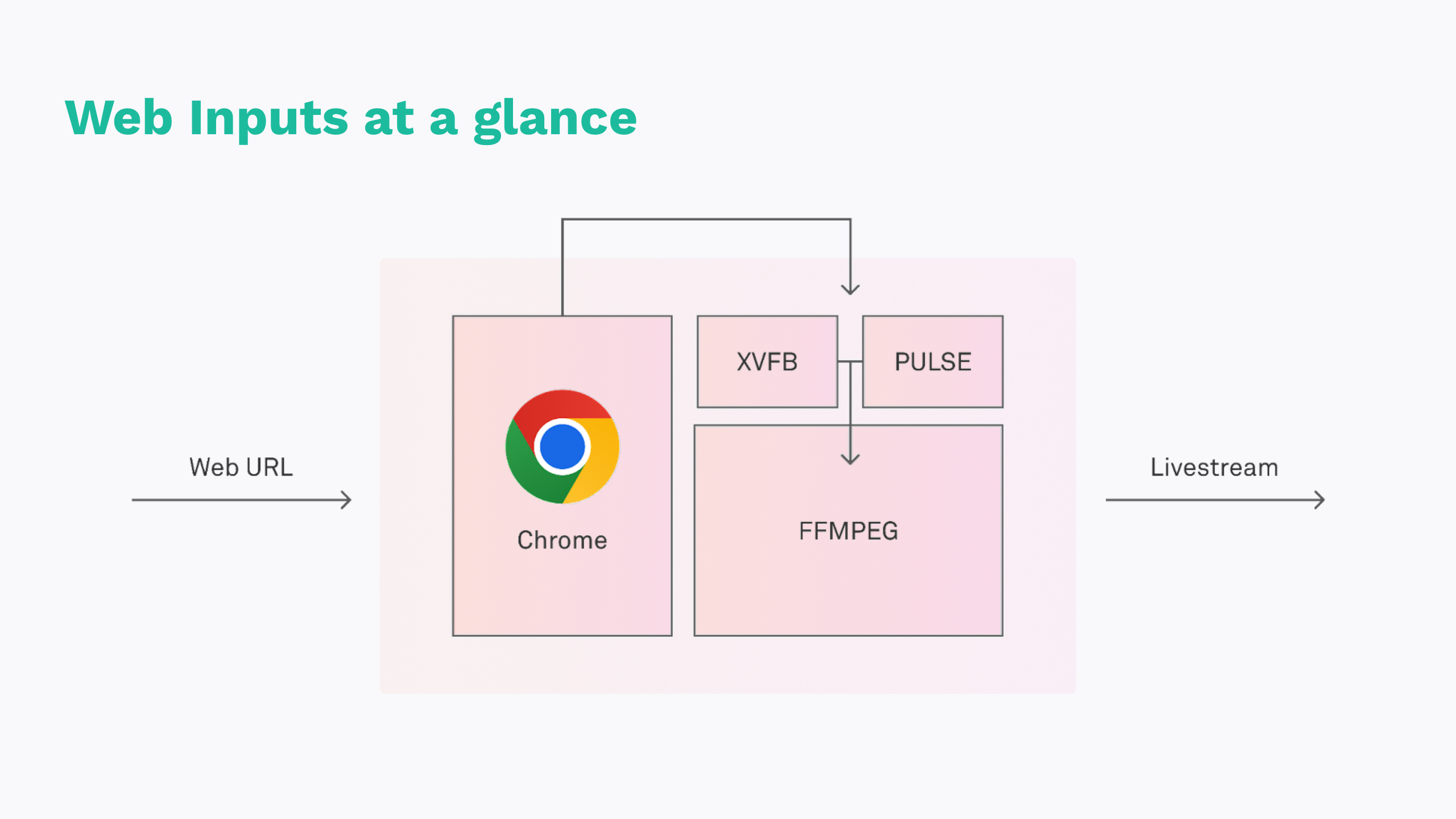

So let’s jump into it. On and off for the last 9 months, I’ve been working on a system called Web Inputs. Web Inputs takes a website URL as input, and outputs a livestream. URL in, video out. On the surface that seems pretty simple, but, as most abstractions do, that simplicity hides a great deal of complexity.

Web Inputs has to wear quite a few hats.

- First and foremost, it runs a headless browser to handle all of the target website’s client-side interaction. For example, broadcasting WebRTC is a common use case, so the headless browser – Chromium, in our case – needs to decode all participant streams.

- Chromium then pushes audio and video onto separate buffers – X11 and Pulseaudio, specifically. We opted to use a virtual X11 frame buffer instead of a canvas to avoid the GPU requirement.

- Finally, FFmpeg can transcode the buffer content and broadcast over Mux’s standard Livestream API.

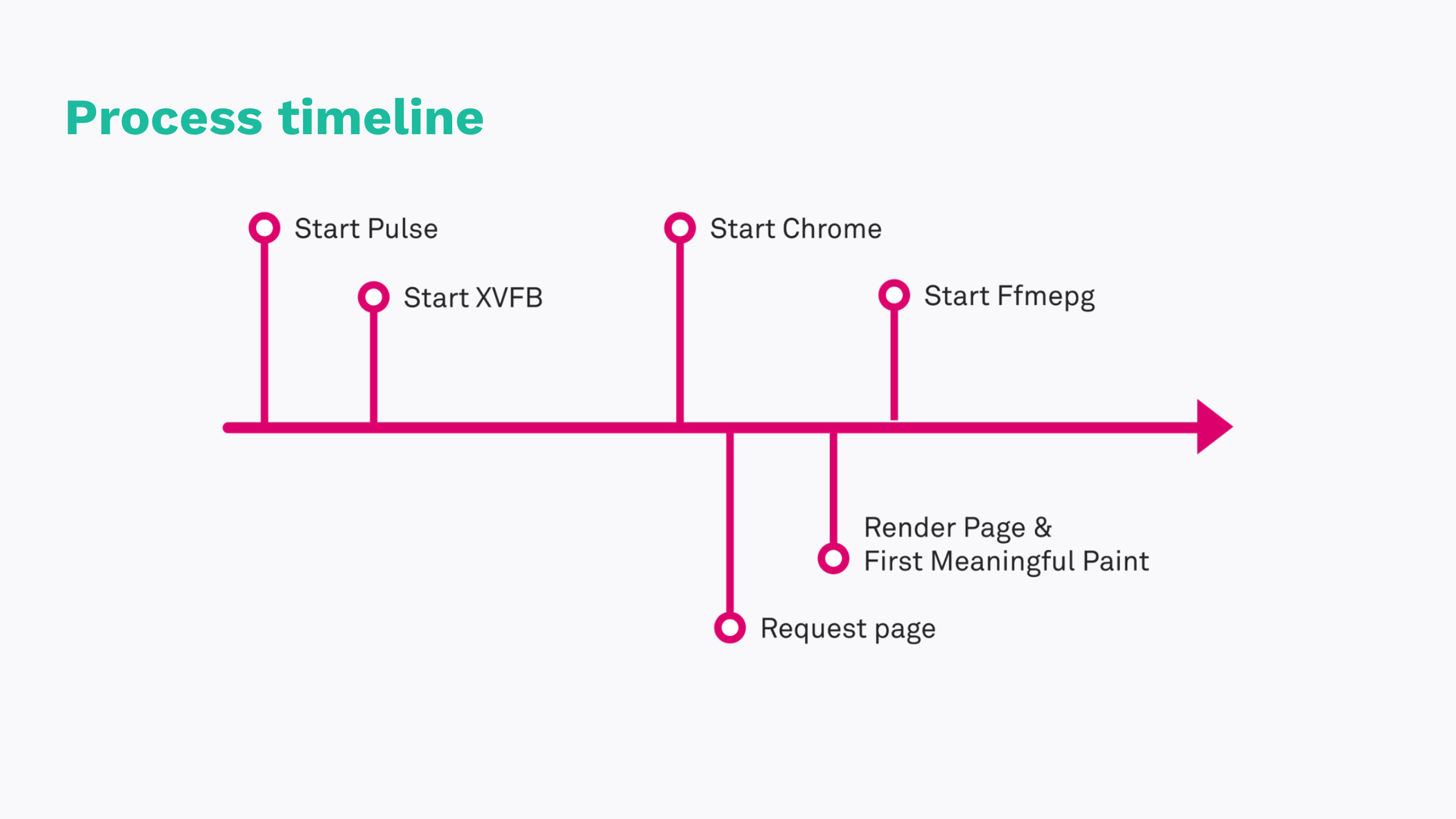

An adjustment we made early on, and one that’s the catalyst for this entire talk, is to hide the page load from the livestream. If we start Chrome and immediately buffer audio and video, we’re going to catch the webpage loading in the resulting livestreaming. That’s not a great customer experience.

Instead, we can listen to Chrome’s events. One of which is called “First Meaningful Paint”, and that’s effectively Chrome saying “something interesting is on the screen now, you should probably pay attention. A colleague of mine, Garrett Graves actually came up with this idea. From a timing perspective, it worked really well, but this change is also when we started seeing some odd behaviors.

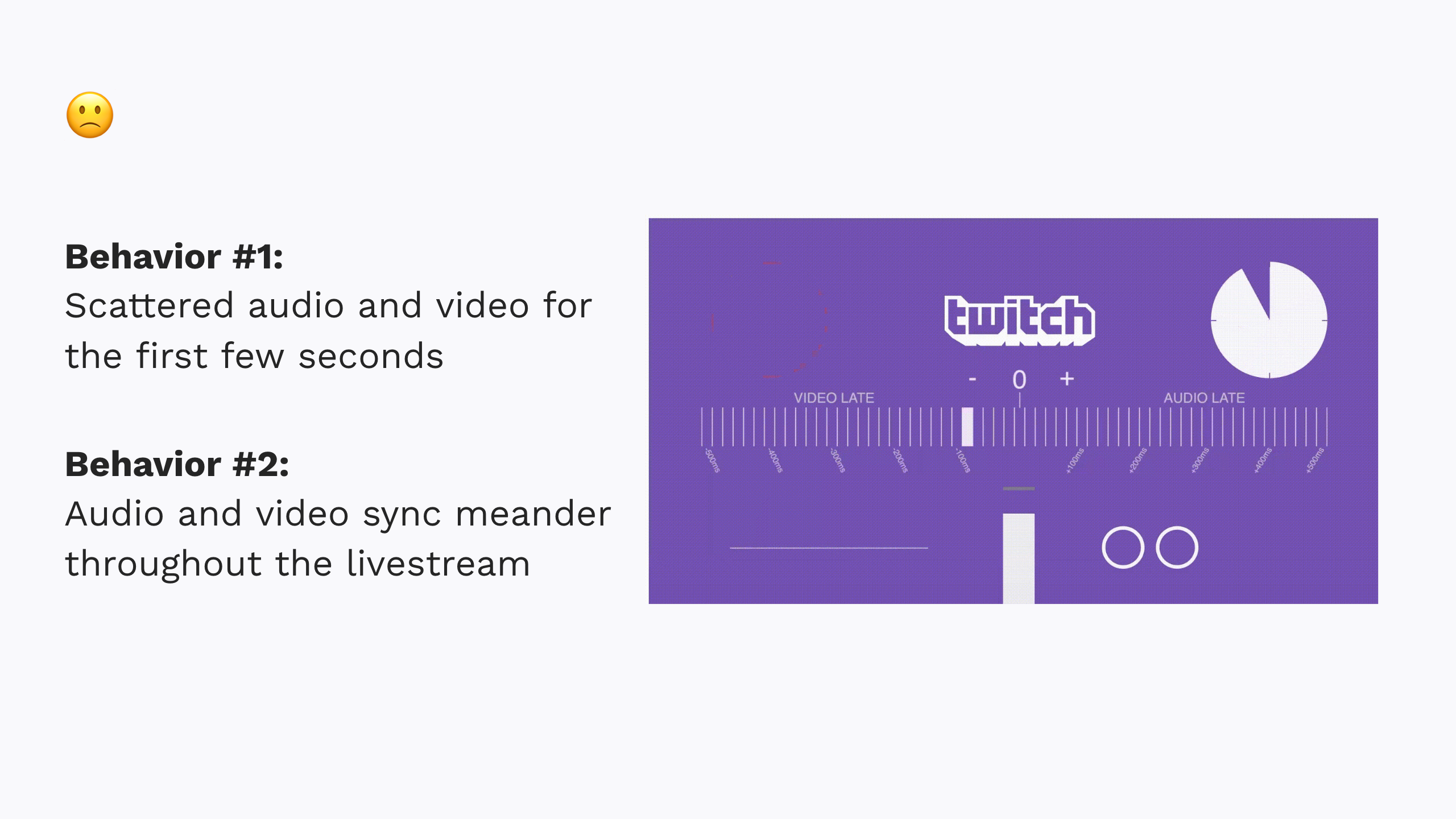

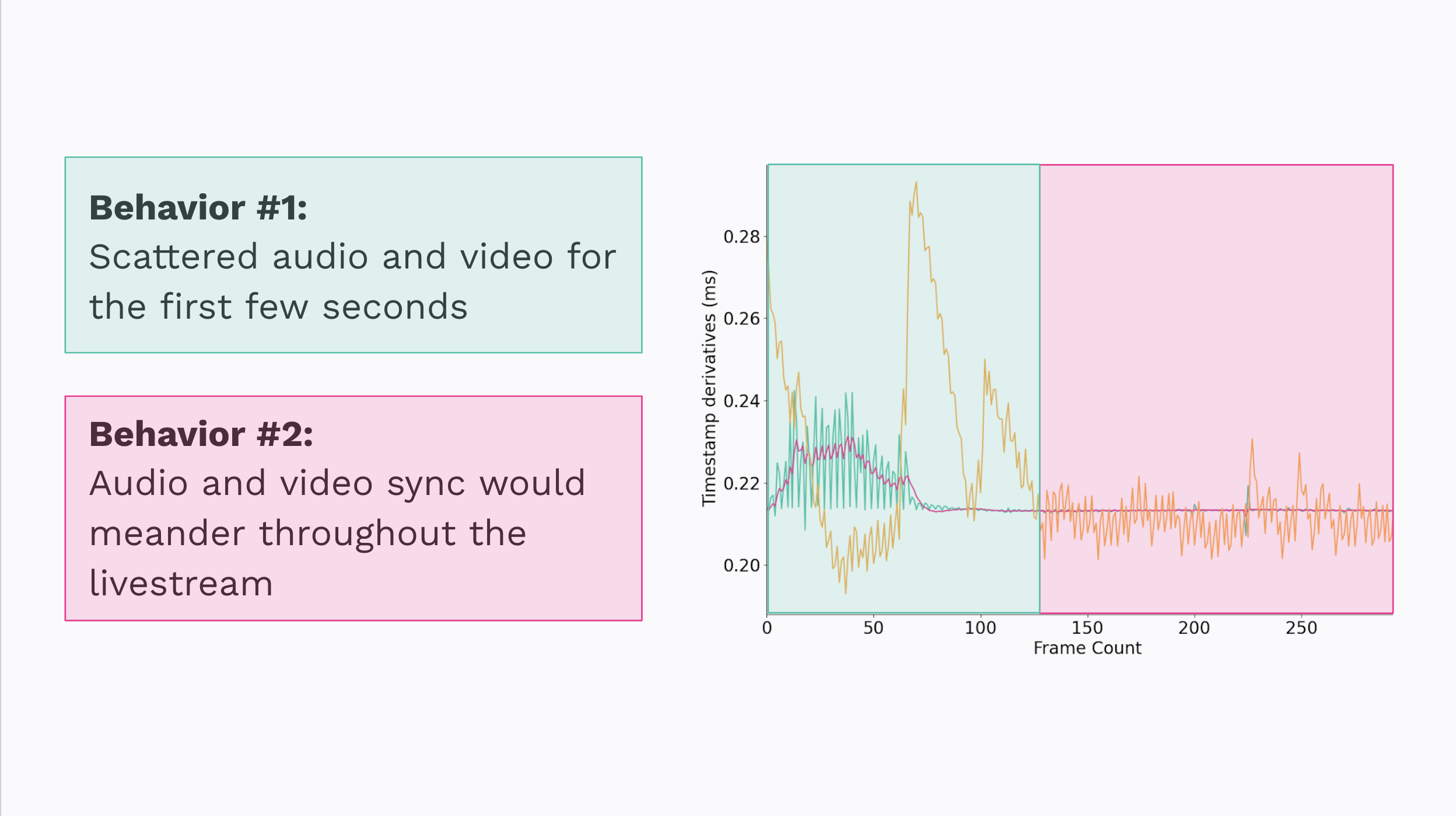

Behavior number 1: the first 4-7 seconds of audio and video looked like they were shot from a cannon. The audio was scattered all over the place, and frames were jumping left and right.

Behavior number 2: the audio + video would meander in and out of sync over the course of the broadcast.

That’s no good. So what did we do? We did, what I’m sure many of you all are guilty of, and stayed up late into the morning fiddling with ffmpeg flags. We read all the blog posts on AV sync. We tried various combinations of filters and flags.

The problem with this approach, as many of you are probably itching to call out, is it lacks evidence. We spent a day on what effectively amounted to trial and error. In fact, a colleague of mine put together a spreadsheet of the flags we had tried, links to the resulting videos, and various, subjective scores.

The most frustrating part: sometimes we’d get close, and I mean really really close. And then one test run would fail, which would put us back on square one.

Another point to call out here: we were testing in different environments. We were comparing behaviors from production against our development stack and the differences were staggering. We allocate Web Inputs some number of cores in production. For context, our entire development stack runs on that same number. It didn’t take long before we noticed how inconsistent dev really was, and that our qualitative assessments weren’t going to get us there.

Empirical evidence is and will always be the fastest way to understanding your problem.

Before we look at any logs or metrics, let’s run through a quick primer on timestamps so we’re all on the same page.

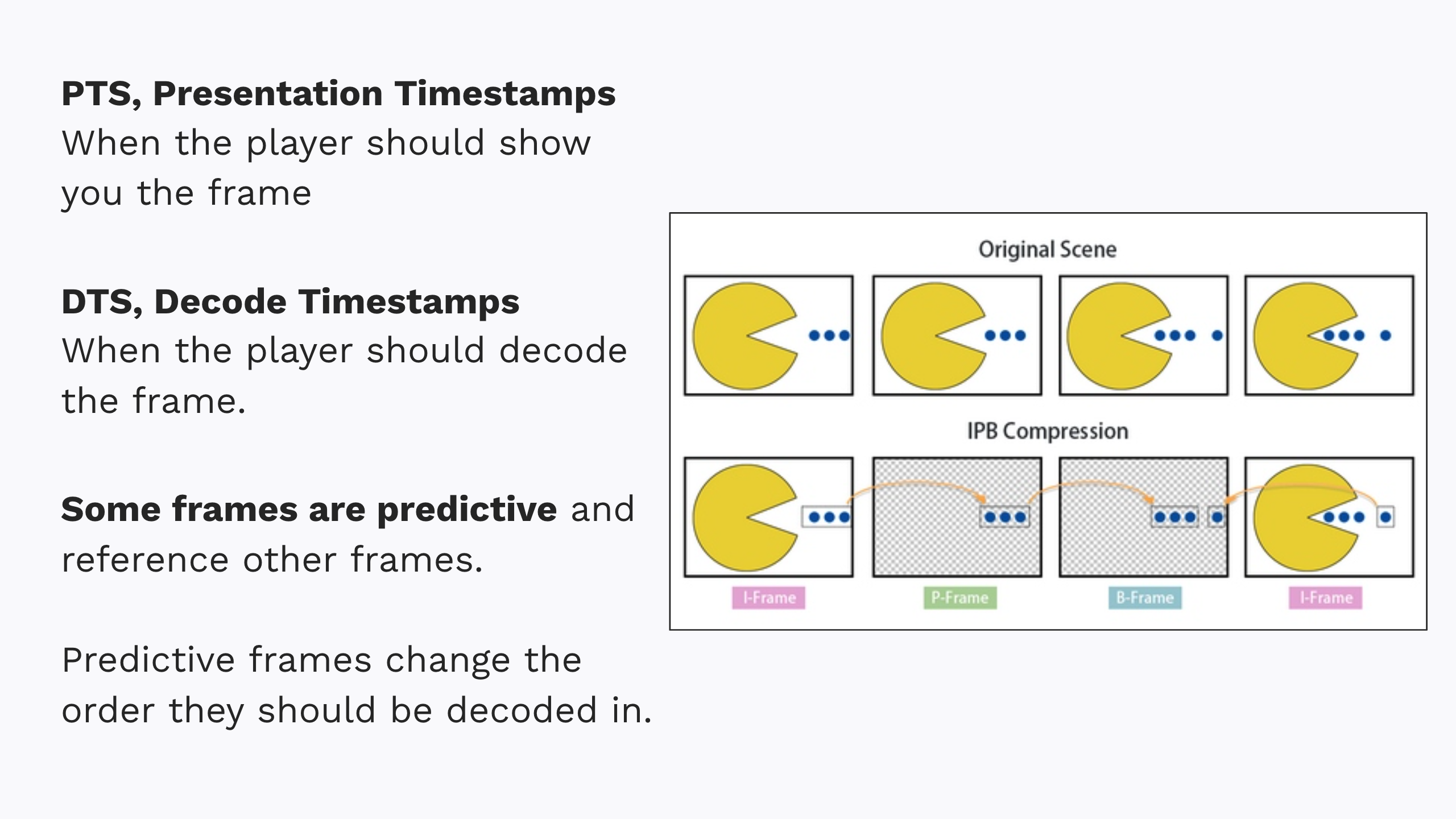

You’ll often hear PTS and DTS talked about – the “presentation timestamp” and “decode timestamp”. For starters, every frame has both and they dictate the frames’ order. The PTS is when a player should present that specific frame to the viewer. The DTS is when the player should decode the frame.

These timestamps are different because frames aren’t always stored or transmitted in the order you view them. Some frames actually refer back to one another. These are called “predictive” or “delta” frames.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about our triage process.

One thing we found early in our investigation: FFmpeg was complaining about timestamps assigned by the Pulseaudio device decoder. Naturally, we wanted to go right to the source, so we added some new log lines to the decoder and dumped various metrics to disk.

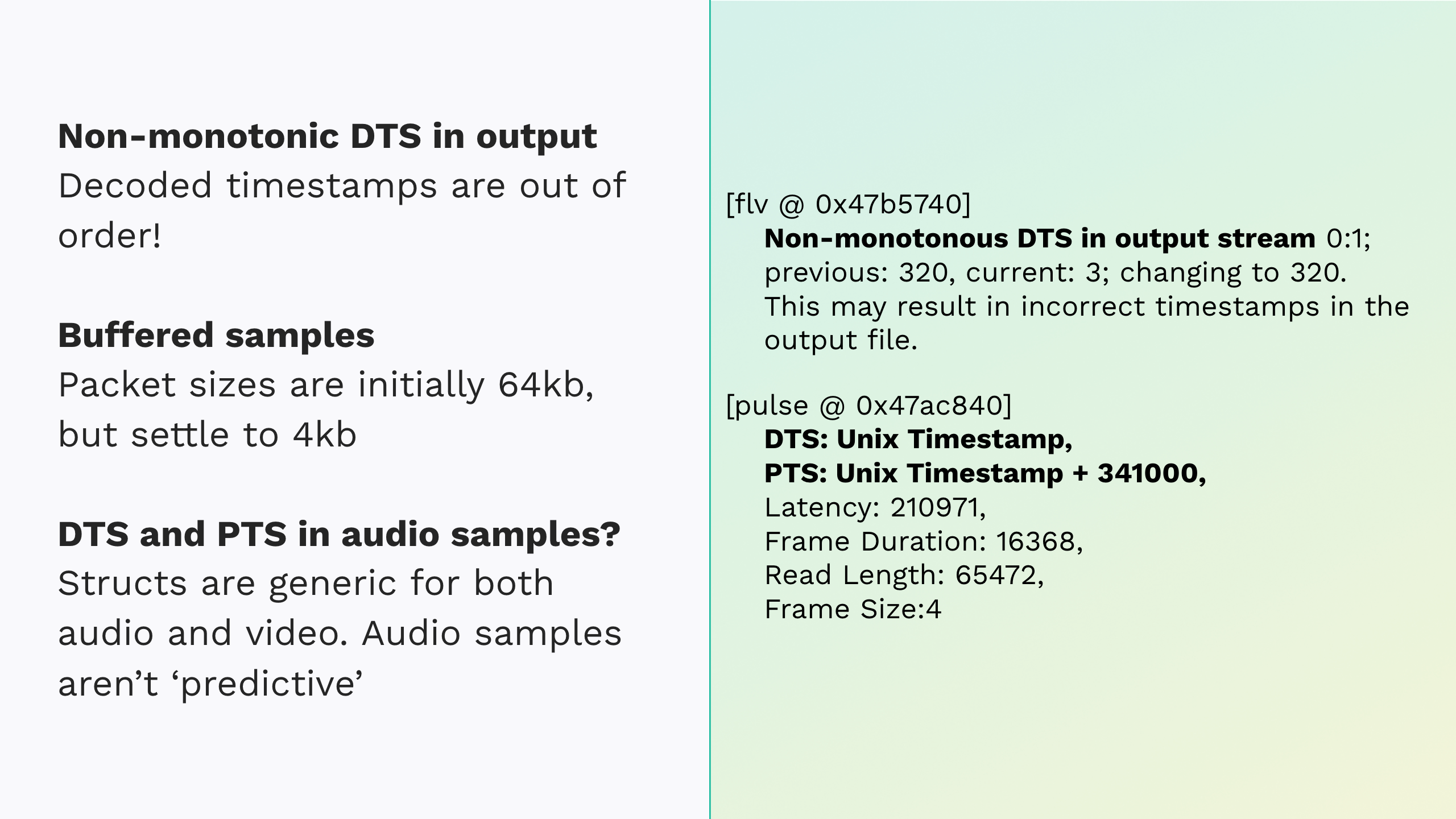

The first thing to call out: “non-monotonic DTS in output stream”. These can be the bane of your existence if you’re not careful. It means that your decoded time stamps are not increasing by the same amount frame to frame.

Another bit to call out are the sample sizes. We’re seeing a huge push of these 64kb packets at the start of the stream, which settles down to a steady 4kb after the first few seconds.

The next bit to question: PTS and DTS on audio samples. Audio ‘frames’ don’t form groups of pictures like video frames do. Audio doesn’t have predictive frames, so why are they used, and why are they different?

Ultimately it comes down to Libav’s data models. Frames and packets are general structs and used for both video and audio, so we can think of “PTS” and “DTS” in this context as ‘appropriately typed fields that can store timestamps’. So that explains why we’re using this terminology, but it doesn’t explain why they’re different.

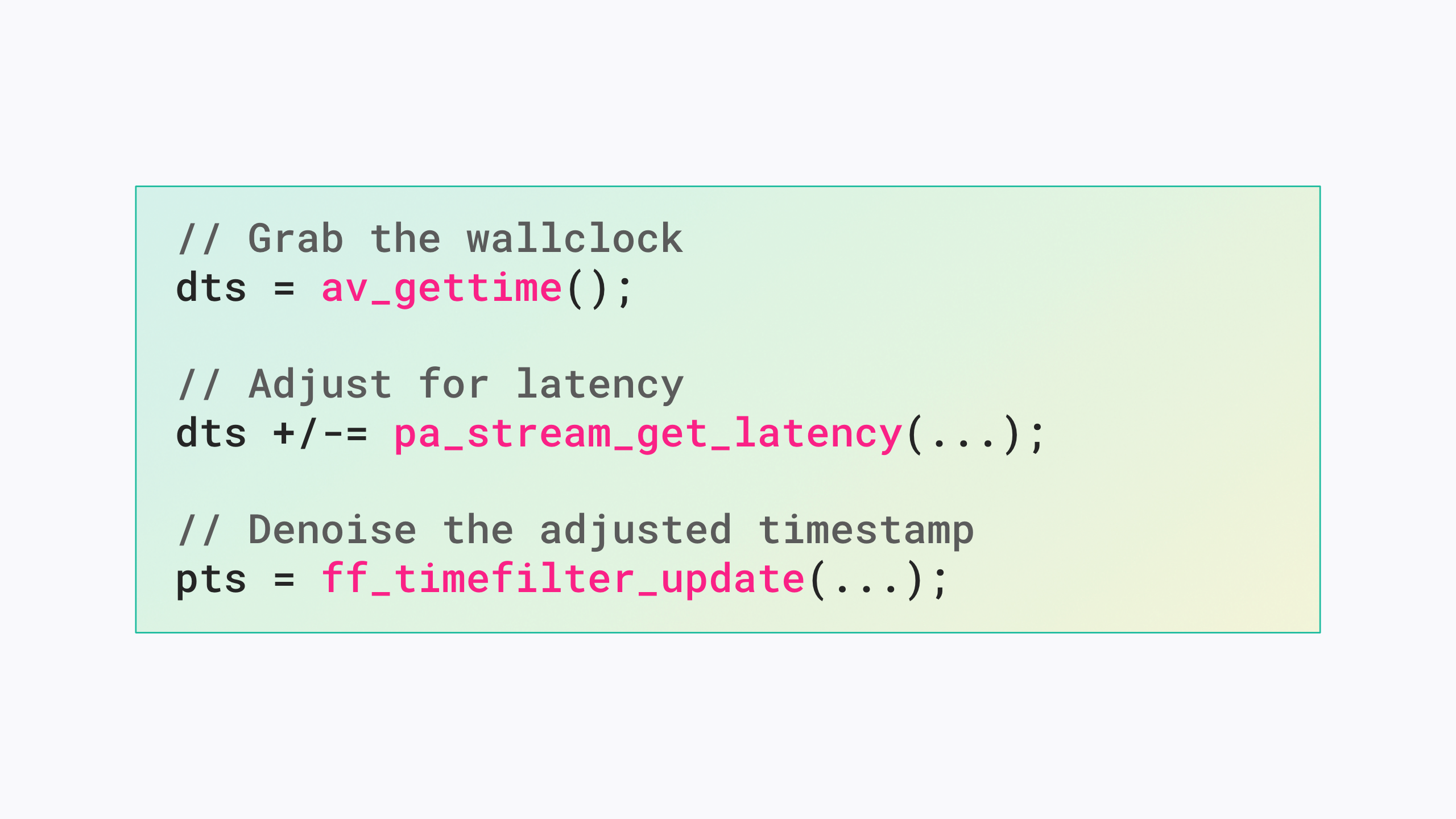

For that we have to look at the Pulse decoder which does 3 things when it assigns timestamps to frames.

The first is to fetch the time according to the wall clock; that’s the DTS. It then adjusts the DTS by the sample latency. That latency is just the time difference between when the sample was buffered by Pulse and requested by ffmpeg.

It then runs it through a filter to de-noise the DTS and smooth out the timestamps frame-frame. The wall clock isn’t always perfect, as we’ll see more of in a second, and it can be exceptionally sporadic in these virtual environments.

Keep in mind, this system is running a docker container, running on a VM, which is probably itself part of a hypervisor. We’re likely not using a hardware timing crystal here, so we de-noise that PTS to offset and inconsistencies.

We’re heading in the right direction, but at this point I’d say we have “data” — not “evidence”. Long log files aren’t exactly human readable, and certainly harder to reason about. I may not be a Python developer, but the one thing I’ll swear by is its ability to visualize and reason about data sets.

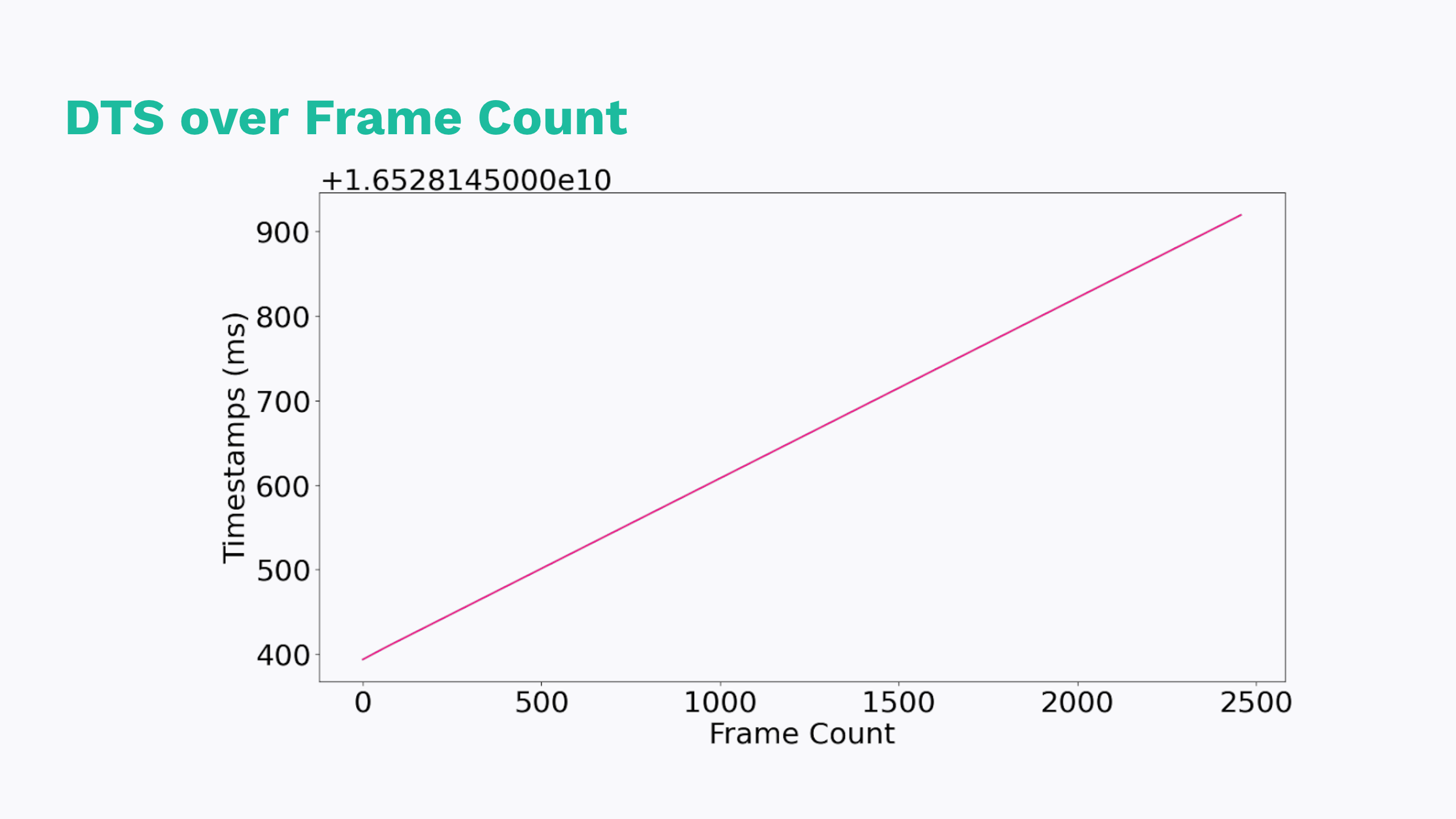

The first thing we wanted to visualize were these timestamps, of course. We expected to see a linear increase in timestamps, maybe an artifact of those non-monotonic logs in the first few seconds.

Good news: we do! But, maybe not as clearly as we should.

Unfortunately, this graph doesn’t tell us that much. We can’t draw any conclusions from this data. What would be more helpful would be to graph the rate at which these timestamps fluctuate because what we really care about is “how reliable or consistent these timestamps are”. The derivative, or the rate of change, of this data might show us how unstable these timestamps actually are.

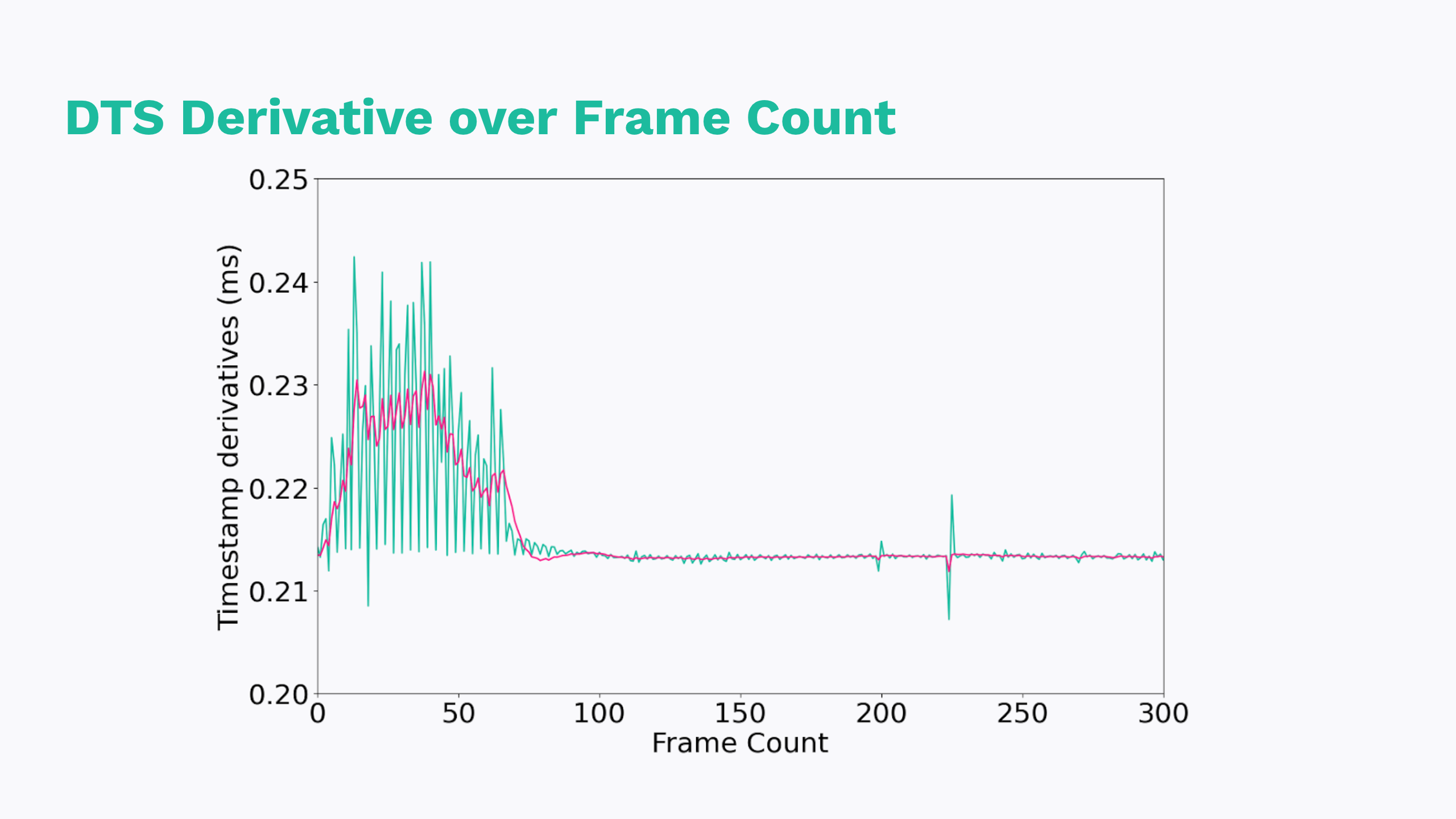

Lo and behold; the derivative is pretty telling. So what are we looking at? Well a derivative of a linearly increasing function is flat, so that tells us that after some number of seconds, our timestamps are dead close to linearly increasing. That’s what we want!

But the first few seconds — they tell another story. Every time the slope increases, timestamps are increasing in a super-linear way. When the slope decreases, our timestamps are slowing down or even “jumping back in time” in a sub-linear way. So that’s interesting, but maybe more interesting is that this is only occurring for the first few seconds.

Also worth calling out is that our denoising filter is doing it’s job, but it can’t spin gold from straw. The peaks are lower and the troughs are higher, but the filter is only as good as the data it’s fed.

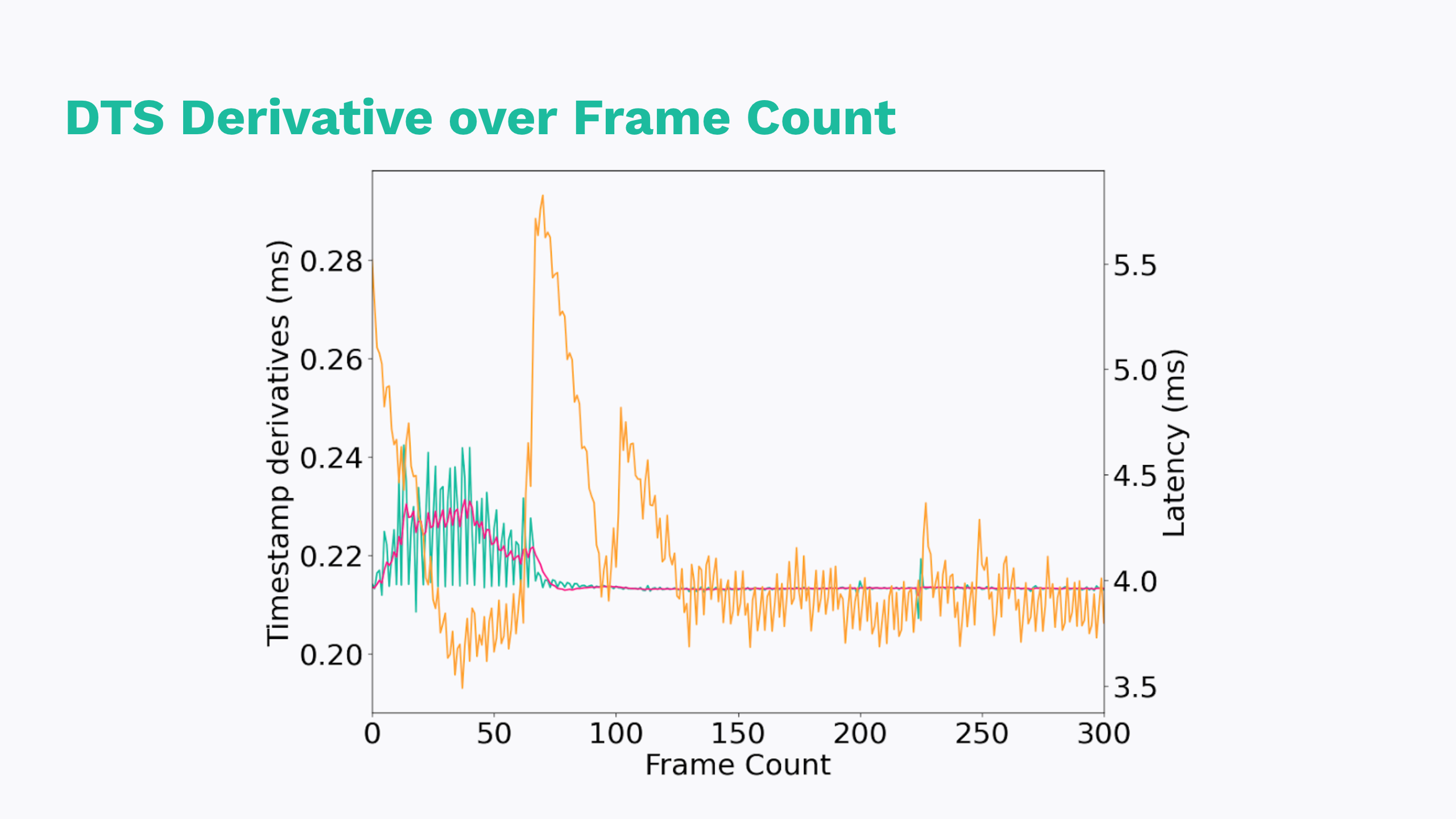

There was another piece to the logs: that back pressure of buffered samples at the beginning of the stream.

If we graph the latency as well, we see some rough correlation. Again, high pangs of latency early in the stream which settles down to something more consistent.

If we think back to those initial behaviors, I think this visualizes them pretty well. We see an initial scramble of timestamps which likely is causing the player to throw frames at us in a seemingly random or unpredictable order. We can also see that the timestamps aren’t perfectly linear, which would explain why AV sync meanders a little bit over the course of a stream.

Something to call out here though: this is just a correlational and not directly causational relationship. These are only part of the picture. It might be hasty to drop the gavel and blame Pulse. There’s a number of paths unexplored here. For example, these are only the audio samples. There’s a whole other side to the video samples to explore.

We needed to step back and consider our goals at this point, though. It’s important to remember that these visualizations are just interpretations – not hard evidence. We, like many of you, are under deadlines.

We had to make the difficult decision here. Keep digging, or action what we already know. We went with the latter, and wanted to strip the problem back to first principles.

Before we talk about how we fixed it, it’s important to talk about what we already knew.

- We already knew that latency was at play, and that Pulse was buffering more than we needed.

- We knew that our timestamps were based off of wall clocks that we couldn’t always trust in this environment (even after denoising).

- We knew some simple metrics like the starting timestamp, exactly how many samples we’ve decoded, and the target frequency.

The first and very naive solution we used to validate our hypothesis was to ignore all samples until we were pulling off nice, round, 4kb packets. This solution gave us fine results in a controlled environment, but we’d never want this hack in production for obvious reasons.

The logical next step here is to flush Pulse’s buffers. If you remember where this entire saga began, we were trying to cleanly start headless chrome without broadcasting the loading screen. Any data buffered before the start of the transcode can be tossed. We found limited success interacting with the audio server directly.

The last option was the one we ultimately went with, which is counting the number of samples and computing the DTS on the fly.

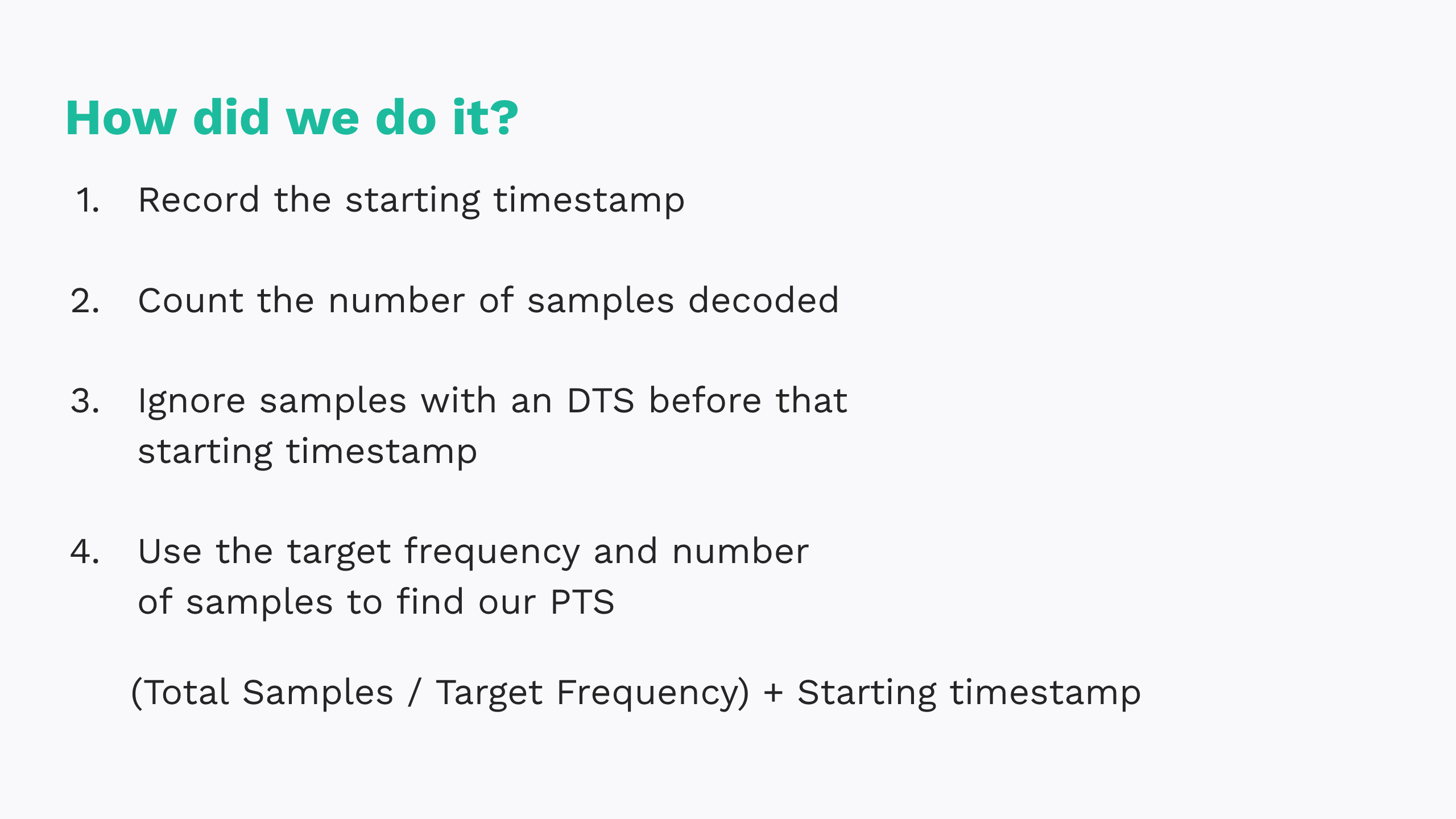

So what does that look like for us? First, we record the wall time when we initialize the device decoder — that’s our ‘starting time’. We then ignore all buffered samples with a DTS before that starting time.

From there, we count each sample we do care about and use that to determine sample perfect timestamps using our target frequency and timebase.

For example, if our target frequency is 48khz, or 48000hz, and we’ve already decoded 96000 samples, that means we’re exactly 2 seconds into the livestream.

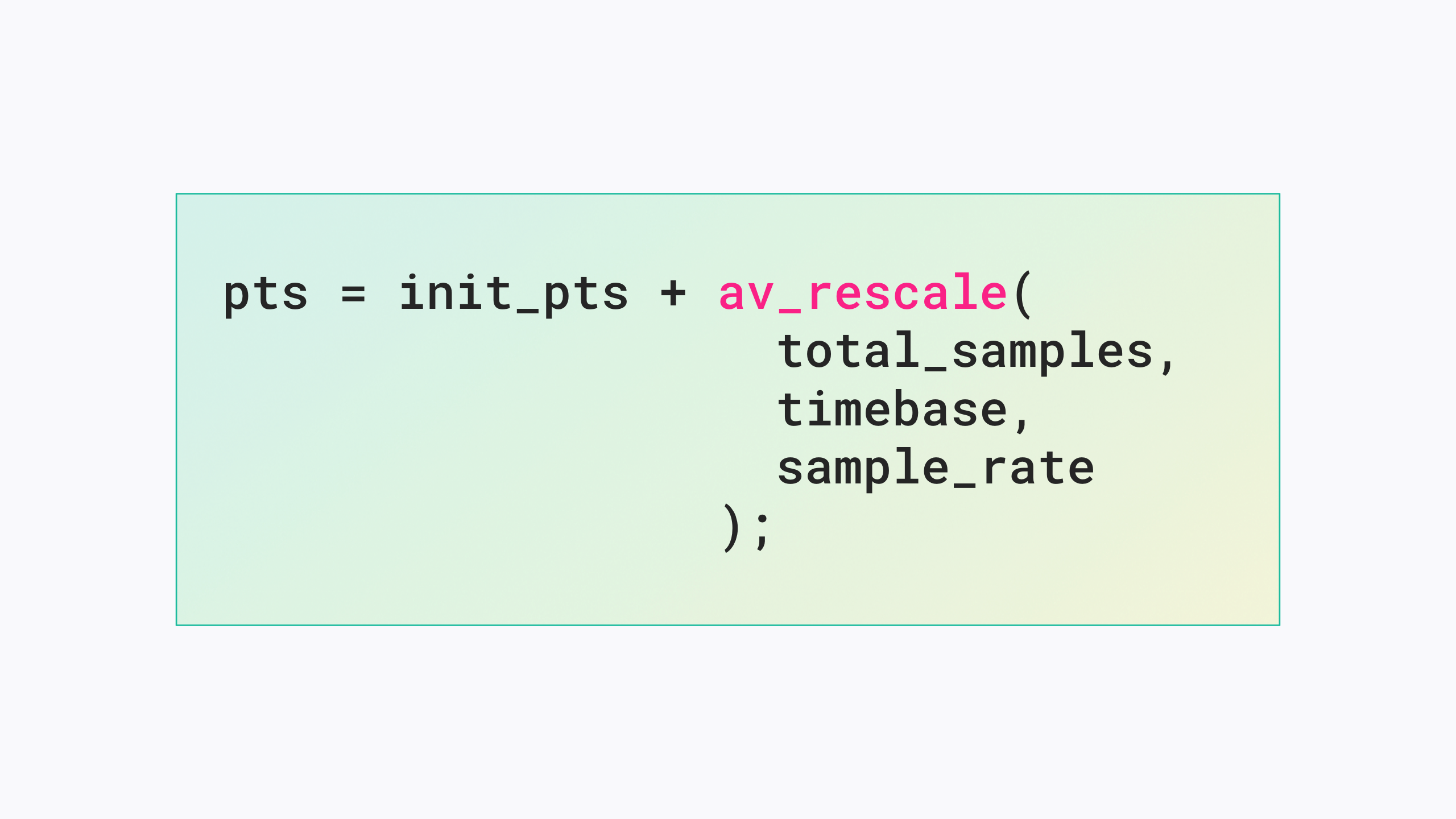

If we translate this solution into terms Libav will understand, it’s actually fairly simple.

The results were so much closer. Not perfect, but closer. In fact, over the next few days, we ran a 8 hour test stream and noticed that, over the course of the day, millisecond by millisecond, the video pulled ahead of the audio.

So, what gives?

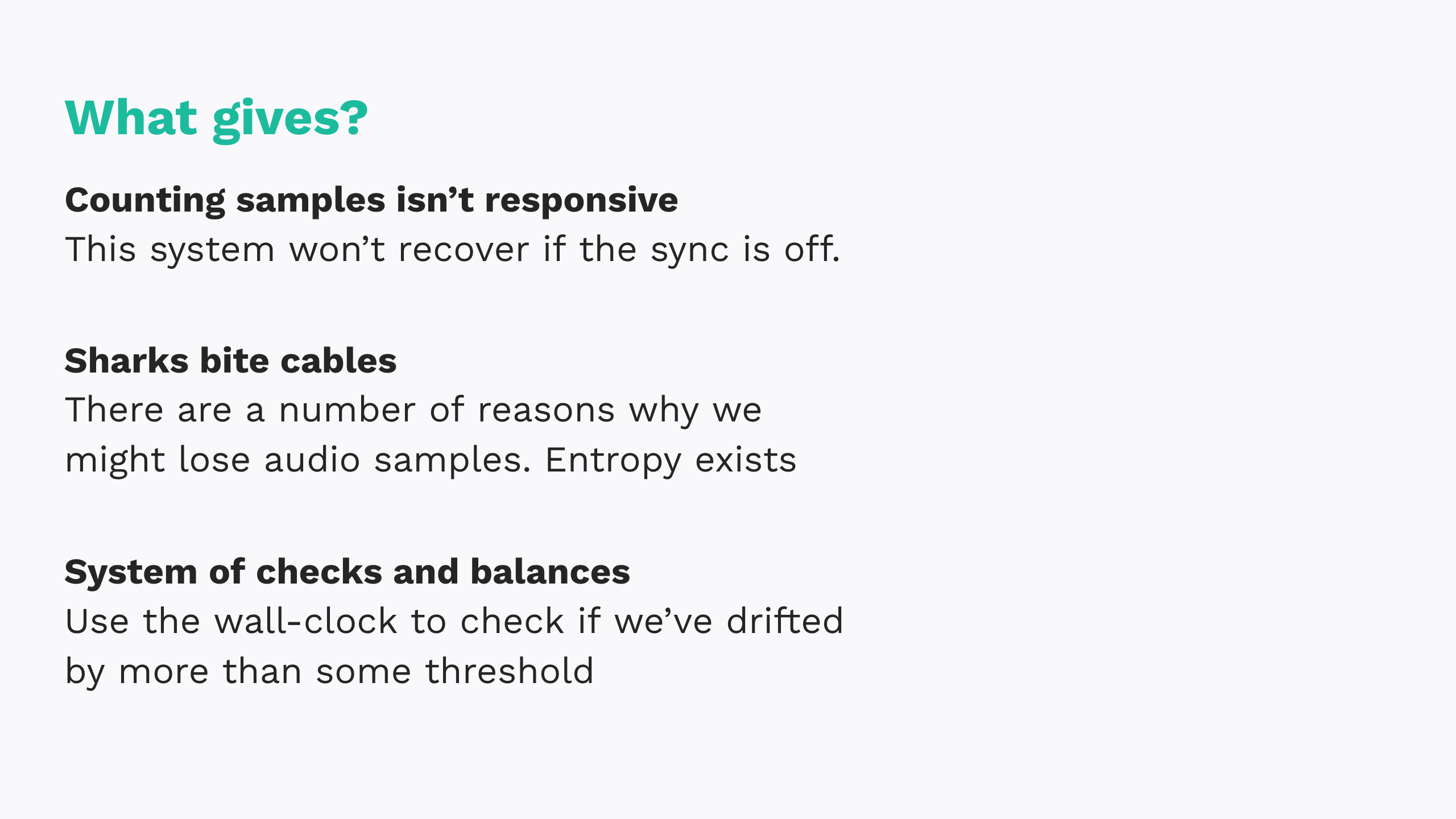

See: what we learned first hand was, when it comes to livestreaming timestamps, you can’t trust any one single method. Counting samples is great in theory, but not responsive by itself. There are a number of reasons why we might drop samples, and this solution doesn’t have any way to recover if we do. Sharks bite undersea cables.

So instead, we can re-sync where appropriate and actually use the wall clock as a system of checks and balances. If the two methods of determining timestamps disagree by more than some threshold, re-sync. You could, for example, reset that initial timestamp and restart the frame counter.

This solution gives you the accuracy of a wall clock but the precision of sample counting.

So what are some takeaways here?

-

For us, this experience was our first time getting our hands dirty with device decoders. We found that, in this instance, going through FFmpeg’s documentation flag by flag wasn’t going to cut it. There’s a big gap in online resources between high level glossary and low level specification. Getting hands on was the only way to fill that gap.

-

Choose redundancy where it matters. This lesson is something we’ve learned in infrastructure and database; video is no different. It’s not always best to trust a single system when calculating timestamps.

-

The last take away, and one that we actually started recently, is to invest in glass-to-glass testing. We wasted far too many hours watching test cards and Big Buck Bunny – my palms still get sweaty when I hear that pan flute.

One thing we tried was injecting QR codes directly into test cards with audible sync pulses at regular intervals. We can then check the resulting waveform to see if those pulses landed on frames flagged with QR codes. We can then use the frame count and sample rate to calculate how we’ve deviated.

That said, I think the big takeaway here is the one I told you was coming from the very beginning: “reliable timestamps in virtual environments are really, really hard.”