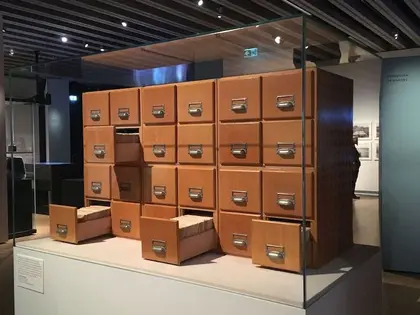

Figure 1: Chris Korner, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach

A few years ago, I stumbled upon a collection of odd websites that called themselves “brain dumps.” On the surface, they seemed like collections of disjointed thoughts – fragments of ideas that linked to seemingly unrelated topics. Often, they bridged disciplines altogether.

That’s when I learned about Zettelkasten.

Zettelkasten

Zettelkasten (sometimes referred to as Zettel or Zet) is a system for taking notes that is specifically structured to develop ideas, not just collect them. The method has existed for hundreds of years under various names, but at its core, it consists of “bite-sized” notes written on slips of paper that are linked by a heading or a unique ID. These slips, often index cards, are filed away in a place that can be easily referenced and traversed.

The theory behind it is sound. Verweisungsmöglichkeiten, translated as a “referral opportunity” or “possibility of linking,” refers to any moment when you might reference another note or tangential thought. For example, ‘structuralism’ might refer to ‘post-structuralism’ which itself links to ‘Michel Foucault’ and a plethora of post-structuralists. Small, pointed notes can connect to any number of these thoughts across various topics, and reviewing your notes often results in finding commonalities among seemingly disparate ideas. With enough notes in your slip box, you can even hold a conversation with it.

In fact, Niklas Luhmann, a German sociologist credited with creating the modern Zettelkasten method, referred to his slip box as a “partner of communication.” His notes comprised just over 90,000 index cards and helped him write nearly 50 books and 600 essays. Luhmann said:

It is impossible to think without writing; at least it is impossible in any sophisticated or networked fashion. Somehow we must mark differences and capture distinctions which are either implicitly or explicitly contained in concepts. Only if we have secured in this way the constancy of the schema that produces information can the consistency of the subsequent processes of processing information be guaranteed. And if one has to write anyway, it is useful to take advantage of this activity in order to create in the system of notes a competent partner of communication.

You can browse Luhmann’s archive online if you’re interested.

Figure 2: The Niklas Luhmann Archive, Historisches Museum Frankfurt

The Spatial and Temporal

In my experience, Zettelkasten felt counterintuitive at first. We, as humans, live and think spatially. Even how we perceive time is geometric. For example, we’ve created the concept of a “timeline.” When you complete a task, you’ve put it “behind you.” When you start a new phase of life, you’re eager to see “what lies ahead.” Humans are inherently spatial – we live in a three-dimensional world – so naturally, our notes are too.

For example, as we read text or listen to a lecture, we take notes sequentially – top to bottom. We indent or nest our notes to show that certain thoughts “belong” to a certain topic. Headers encapsulate subheaders, similar to how rooms encapsulate closets (which themselves have drawers and boxes, etc.).

Zettelkasten, however, avoids concepts of past, present, and belonging. Notes aren’t concerned with what came before or after them, only how individual thoughts relate to one another. They juxtapose and correlate ideas, rather than spatially positioning them. The value of a note isn’t in its individual content, but in the narrative they collectively tell as you discover new paths between and bridges across topics.

Luhmann, too, valued this idea of “internal branching”. New ideas shouldn’t be appended to a list of prior notes, but instead inserted among connected thoughts. This internal network of links creates a greater combination of thoughts than if we simply connected thoughts to what came before and after.

Deleuze, Plato, and Rocking Chairs

Last year, a colleague introduced me to a group of post-structuralists, including Derrida, Deleuze, and Baudrillard. Deleuze particularly caught my attention with his interest in topology. Relevant to this essay is his disdain for representational thinking and strict hierarchy.

To properly understand Deleuze, we should probably first understand Plato. Plato believed that everything has an ideal form, and the closer something is to that ideal form, the closer it is to perfection. For example, there is an ideal chair, and so a chair with a slight wobble is closer to perfection than a chair with a broken leg.

Deleuze describes this model as “arborescent”; it is structured like a tree, where the ideal form is the root and the lesser representations extend out over the branches to the canopy.

In our “chair” example, somewhere on that tree are stools, stumps, and hammocks. They are ranked according to their proximity to the ideal chair. Plato might ask, “How perfect of a chair are you?” but Deleuze took issue with this line of reasoning. He proposed that a better question is “How are you different?” or “What characteristics make you unique?” We can then categorize the stump, stool, and hammock not by their representation of an “ideal chair,” but by the differences between them. Stools are portable, hammocks are soothing, and stumps firmly ground you in nature.

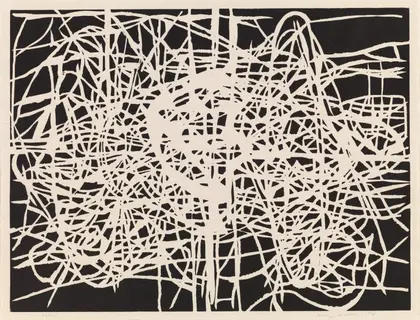

Figure 3: Terry Winters, Rhizome, 1998, Smithsonian American Art Museum

In contrast, Deleuze calls this “rhizomatic” thinking. Rhizomes are systems of roots that spread horizontally underground and branch in every direction. Ginger and asparagus are rhizomes. They have no top or bottom, no start, and no end. They are circuitous and cyclical. If you kill one section, the remaining roots will live on. If you cut it in half, they will live separate lives.

Relative to arborescent thought, in a rhizome nothing represents something else and certainly not an ideal form. In rhizomes, all that exist are the connections between nodes. Stools are chairs without a back. Chairs are hammocks without a rotating axis. Hammocks and rocking chairs incorporate motion.

Zettelkasten are also rhizomes. My notes for this essay point me towards Spinoza, then to Pantheism, then to Sikhism, then to Buddhism, then to the concept of time, which itself inspired my earlier point that humans perceive time spatially. They branch, reconnect, wind, and are never hierarchical. They are, if we want to think spatially, horizontal.

Repetition and Paratext

There is another connection between Deleuze and Zettelkasten worth exploring, and that is repetition. Deleuze believed that when you repeat something, you are creating a copy of that thing. When you think about a rocking chair, you are creating another representation of that chair – one that differs in many ways from all the rocking chairs you have seen before. Therefore, by rereading or repeating your notes, you are creating a unique multiplicity.

The problem with this is that your notes do not exist in a vacuum. They are, if transcribed linearly, surrounded by prior context. They are spatially dependent on adjacent ideas – how the topic is presented, the previous lecture, the syllabus as a whole, and even the notes on the chalkboard. This framing is paratextual; it informs how you approach the primary text, similar to how the cover of a book or the font on its spine might.

When you repeat or review linear, contextual notes, you are creating a snapshot of a previous argument – paratext and all. You are retracing the same ground and connecting the same dots. This repetition cannot lead to the creation of new ideas.

Deleuze dislikes representational thinking, in part, because we cannot create anything new if everything represents a common root or a perfect form. yourself the opportunity to reframe those thoughts. You are not just rehashing the same ideas in the same light; you are creating an entirely new amalgamation from existing scraps. You will find more opportunities for external connection – verweisungsmöglichkeiten – and therefore more opportunities to evolve and transform your existing ideas.

Luhmann found it extremely important for communication partners (you and your notes, in this case) to “mutually surprise each other.” Partners can only successfully communicate, or produce new information, when they “communicate in the face of different comparative goals.”

In closing

So why am I writing this? It was, for all intents and purposes, a proof of concept; a successful conversation with my “communication partner”.

In fact, the majority of time spent writing this piece was spent on flow, grammar, and narrative. I took the bulk of the content from a series of notes written on disparate topics at various times over the last year.

The graph now has enough nodes – the rhizome enough roots – that I’m surprised by new connections. I can follow trains of thought longer than a few nodes. I can venture forward, backpedal, and reconsider thoughts I had from months prior. No note has a perfect form. No note is dependent on time or space. No note is dependent on another.

In all honesty, I’m not sure where this train of thought should end, or if it should end at all.

Maybe in the future, I’ll write something more concrete on how exactly I take notes. For the time being, I’m still working out the finer details. I’ll update this conclusion with “new nodes” as they are written.

References

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Literature, Culture, Theory 20. Cambridge ; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Luhmann, Niklas. Communicating with Slip Boxes. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://luhmann.surge.sh/communicating-with-slip-boxes.

The Rhizome - A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari. Then & Now, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQ2rJWwXilw&ab_channel=Then%26Now.